The LRRPs were a link to America’s military past, but they would also become a bridge to its future.

By Gary P. Joyce

“Let the enemy come till he’s almost close enough to touch. Then let him have it and jump out and finish him off with your hatchet.” That was one of the standing orders for Rogers’ Rangers in 1759 for combat operations during the French and Indian War in the forests of New England. More than two centuries later, that same approach would serve their successors well during combat operations in the jungles of Vietnam.

Hunters and Trackers

The long-range reconnaissance patrols (LRRPs) of the Vietnam War operated in a silent netherworld of dark green shadows where error could mean death and where the extraordinary was commonplace. Traveling in small groups —often only three or four men —far from friendly forces, they strove to look, smell, move and act as much as possible like the enemy they sought in the depths of the jungle. LRRPs were hunters and trackers, and their elusive prey was the NVA and VC.

They were adept at the art of ambush, the quiet kill, unseen movement and survival. They wafted through the jungle like a solitary breeze, briefly felt, quickly gone. They were the eyes and ears of a roaring, earth-splitting, technological typhoon of destruction —the killing machine that was the U.S. military in the Republic of Vietnam.

The LRRPs —a small, unheralded, elite force of specialists in guerrilla warfare —were an all-volunteer group of soldiers with a minimum of formal training in the skills of covert counterinsurgency operations. Nevertheless, they had an effect on the overall military operations in Vietnam that was completely out of proportion to their number.

Adopted Tactics

The war in Vietnam presented the American military with a task it was initially not prepared to carry out. Focused on the Cold War and conventional conflict with the Soviet Union, military strategy during the years preceding Vietnam had depended largely on high-tech weaponry, where the tactic was to throw enough money, equipment, troops and firepower at an enemy to overwhelm him. Faced with the prospect of protracted jungle warfare in Southeast Asia, America’s military leaders were forced to return to less conventional tactics —some of which had been pioneered long before the 20th century.

The long-range patrol concept — sending small groups of men far into enemy territory to harass, interdict, wreak havoc and gather intelligence while remaining undiscovered — was not new. In American history, it can be traced back to the beginning of the French and Indian War in the mid-1750s, when then-Colonel George Washington wrote, “Indians are the only match for Indians.” New Hampshire woodsman Robert Rogers joined a scout company during the French and Indian War and was eventually promoted to major and commander of nine so-called “ranger” companies. Using marching orders that are still issued to U.S. Army Rangers today, the original Rogers’ Rangers were successful in their harassment of the French along the Hudson River because they adopted the Indian skills of stealthy approach, ambush and woodcraft during their raids.

America’s Ranger Heritage

Those same unorthodox tactics were espoused by contemporary military men from other nations, as well. Colonel Henri Bouquet, a Swiss mercenary employed by the British, wrote that the war fought in the wilds of the New World required that “troops destined to engage Indians must be lightly clothed, armed and accoutered …” Although Bouquet was speaking of troops in company-size strength, the new tactics — considered heretical in an era of massed troop formations —were catching on. To fight natives on their own soil, do as they do — act like them.

The American Revolution saw fast-moving, lightly equipped guerrilla forces led behind British lines by men such as Colonel Francis Marion (the famed “Swamp Fox”), Thomas Sumter and Andrew Pickens. As would happen again and again in future wars, those irregulars were laughed at and virtually ignored by the conventional military early in the conflict. But it would be the guerrilla raids of Patriot partisans between 1780 and 1781 that eventually countered the British strategy in the American South and led to the surrender at Yorktown.

Some 80 years later, during the Civil War, the Confederacy put irregular forces to use on a regular basis. Southern leaders such as John Hunt Morgan, John Mosby and Nathan Bedford Forrest frequently ranged along the flanks of and far behind the Union forces. Asked about his tactical successes, Forrest replied succinctly, “I always make it a rule to get there first with the most men.”

The Indian Wars brought to public notice Indian leaders such as Sioux warrior Crazy Horse, Nez Perce warrior Yellow Wolf and Apache warriors Mangas Coloradas, Cochise, Nana, Victorio and Geronimo —skillful fighters who knew how to make use of guerrilla tactics better than any of their white opponents. On the whole their forces were too fragmented to put forth a cohesive effort, but even though they were constantly pursued, usually outnumbered and possessed inferior arms, some groups still managed to hold out against U.S. Army Regulars into the 20th century.

Modern Ideas About Patrols

World War II brought the concept of patrols working and living in the backyard of the enemy into the modern era. “Twenty men is a good number to work with, but 15 is better than 20, and at night 10 is better than 15,” declared British Brigadier Orde C. Wingate, organizer of the so-called Gideon Force, a fast-moving commando unit that adopted hit-and-run tactics during the North African campaigns early in World War II.

Wingate’s mercurial personality (later histories would call him — at best — mentally unstable. See Max Hastings Inferno: The World at War 1939-1945.— GPJ 11/5/19).”kept him at odds with the military establishment of his time, but the successes of the Gideon Force against the Italians in Sudan and Ethiopia proved to many that the concept of a lightweight force worked. Many military strategists of the time, firmly rooted in traditional warfare tactics, disregarded Wingate’s methods, but the British commando leader pursued the concept nevertheless. After he outlined his ideas on what he termed “long-range penetration” in a formal paper to the British high command, he was given another opportunity to put the concept into action in Burma in 1942.

Wingate believed that small groups of troops (small connoted brigade-size at that time), working in the rear of the enemy, supplied by air and in communication with main force commanders, could tie up enough enemy manpower to aid regular military operations within the theater. Wingate’s Raiders —more commonly known as Chindits —put his theory into practice during their operations against the Japanese in northern Burma in 1943. During this period the acronym LRP —long-range penetration —showed up in military parlance for the first time.

Some strategists maintained that the Chindits failed to sufficiently weigh the operations in which they were involved —at least to a sufficient degree to convince traditionalists of their effectiveness. Certainly the Chindits’ success was achieved at a high cost, since many lost their lives in Burma. But their actions proved to many that quasi-guerrilla forces were an operational necessity in certain theaters of war.

(Later histories from the writing of this piece, say that these and the following WWII special force units — perhaps with exception of the Gurkhas — were more a public relations success than a military one. — GPJ, 11-5-19)

Independent Raiding Companies

As the Chindits slogged their way through the tortuous terrain of Southeast Asia, the British army started forming independent raiding companies, forerunners to the British Commandos, immediately after Germany overwhelmed France in the spring of 1940. In the Pacific Theater of Operations a cadre of Anzac (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) instructors, together with a small British army training contingent, formed a company out of the Dutch and Australian forces stationed on the island of Timor —the 2/2 Independent Company. One of the British soldiers, Captain F. Spencer-Chapman, said that the six weeks of special training taught the volunteers “how to get…from A to B and back…in any sort of country…what to wear, what to take and how to carry it…tracking, memorizing routes, and how to escape if caught by the enemy.”

Organized as a 350-man-plus company-scale operation, the 2/2 Independent Company confronted a 14,000-man Japanese invasion force on Timor in February 1942 and was overwhelmed. Instead of disbanding or surrendering, however, the never-say-die Australians fell back, regrouped in the hinterlands of the island and started working against the Japanese in groups as small as two, three and four men. In 13 months of operations following the invasion, the 2/2 killed more than 1,500 Japanese soldiers while losing only 40 of its own.

Merrill’s Marauders

In 1944, the Americans formed an LRP group to which Vietnam War LRRPs officially trace their lineage. Merrill’s Marauders —the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) —had originally been assigned to Orde Wingate but were transferred back to American command under General Joseph Stilwell. Then-Colonel Frank Merrill headed up the unit. In a joint offensive with Stilwell’s Chinese troops, the Marauders circled 100 miles behind the Japanese stronghold in Burma, cut supply lines, captured part of a Japanese division, and reached the main Japanese base at Myitkyina. There, they captured the airfield and, after joining with Stilwell’s troops, secured the town. The regimental-strength Marauders experienced the same difficulties that the Chindits had faced in the terrible climate and topography of the Burmese mountain jungle. Merrill himself was evacuated twice, once for heart problems and once for malaria, and the rigors of moving a large force through the Burmese terrain severely debilitated his troops. The unit operated for just over three months before being deactivated.

Despite their limited successes, the Marauders, Chindits and Independents planted the seeds that would eventually come to fruition in Vietnam. The LRP concept had proved successful. Although all three groups were organized as large-scale, behind-the-lines forces, the 2/2’s jungle-fighting preparation was of a considerably higher quality. The Chindits were better trained specifically for the jungle than the Marauders were, but both Chindits and Marauders used regular infantry conscripts who had a minimal amount of jungle warfare training. The Chindits and Marauders tended to maintain the regimental size of their units rather than disperse into smaller operational groups as the 2/2 Independent Company did. As those units’ missions in the mountain jungles of Burma and Timor came to an end, other small-unit strategies were implemented.

The Jedburghs

In the European theater, Jedburgh units, comprised of two officers and a sergeant radio operator —either French, British and/or American —were dropped behind enemy lines to train and assist French Resistance forces prior to the Allied landings in Normandy. Another type of unit, known as Operational Groups (OGs), infiltrated 32-man airborne commando units into France that operated in eight-man teams. Jedburghs and OGs were most active before the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, and both types of operations were fairly successful.

The idea for both units came from the Special Operations Executive (SOE), Britain’s version of the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of today’s Central Intelligence Agency. Both units proved that small-unit operations were, indeed, able to succeed. But although their employment of the small-unit concept was a plus for the Allies during World War II, both the SOE and the OSS were also partially responsible for other postwar phenomena that would plague the West for decades. The SOE and OSS considered themselves nonpolitical organizations; their World War II objective had been simply to beat the Axis forces. Consequently, they armed any and all groups that would fight the Germans or Japanese, regardless of their political complexion. In so doing, they helped several Communist insurgent movements that they would have to fight after the war. The SOE, for example, gave weaponry to Communist-oriented insurgents it would eventually have to battle in Burma and Malaya. The OSS was no less generous to Mao Tse-tung in China, and it also armed the followers of a well-educated Communist and nationalist named Ho Chi Minh in the French colony of Tonkin.

Wars Begin in Indochina

On September 11, 1945 —nine days after the formal surrender of Japan —the first of three modern wars began in Indochina. The first, called the August Revolution by the nationalist and Communist Viet Minh, is historically interesting if only for its brevity and anonymity. The British Gurkhas —Nepalese troops who were excellent irregular jungle fighters in their own right —of the 20th Indian Division, together with rearmed Japanese troops, decimated a Viet Minh nationalist force that had tried to assume power in the absence of any occupation force organized by its former French colonizers. That conflict saw the capture of the first Soviet adviser to the Viet Minh (who later disappeared after being turned over to the French Sûreté).

The war began when the Viet Minh attacked the Gurkhas at a village called Tan Son Nhut and ended when the British handed the country back to the French in early 1946. In five months, British forces killed an estimated 2,700 Viet Minh while suffering minimal casualties.

Two organizations that spanned the next two Indochina wars also left their imprint on the LRRPs. One was the French army’s Groupement de Commandoes Mixtes Aeroportes (GCMA), or Composite Airborne Commando Group. After December 1953, it was known as the Groupement Mixte d’Intervention, or GMI, and it directly influenced the operations of the American 1st Special Forces Group, the famed Green Berets, of the Second Indochina War. The Special Forces, along with Anzac Special Air Service (SAS) troops, added their concepts to the LRRP tactical mix.

New, Guerrilla-Like Mode

The GCMA functioned in a more guerrilla-like mode than any other organization. Its members were dropped into enemy territory to organize local mountain tribesman to fight the Viet Minh. The unit eventually grew to some 15,000 troops, which meant that more than 300 tons of airlifted supplies were required per month. Unlike the Chindits and the Marauders of WWII, the GCMA’s job was to remain permanently behind enemy lines. Each company was led by two or three French officers or noncommissioned officers —the remainder were native tribesmen.

The GCMA tied down 10 battalions of Viet Minh troops, and by the end of the French Indochina War the 5,000 remaining GCMA members were being hunted by 14 Viet Minh battalions. The long-range penetration principles Wingate had espoused nearly 15 years earlier had finally been convincingly proven effective.

The GCMA saga ended in a July 1954 cease-fire between the French and the Viet Minh. The last French troops left the area in April 1956. Two years after the cease-fire, a GCMA leader’s radio plea was monitored, requesting “at least some ammunition, so that we can die fighting instead of being slaughtered like animals.” As late as 1959, a GCMA trooper made his way out of North Vietnam, but the rest of the French troops trapped behind the lines fought to the death, and their final resting places were never discovered by the French government. (See “To Die Alone in the Silence,” by Robert Barr Smith.)

America’s Special Forces

The GCMA proved that irregular warfare could work. The American 5th Special Forces Group in Vietnam took the lessons learned by the GCMA and the WWII guerrilla units, refined the techniques and put together a highly successful military operation.

The Special Forces were initially conceived as a GCMA-like guerrilla group. It was not until President John F. Kennedy took a shine to the counterinsurgency principles of modern warfare and discovered the Special Forces, which had been lingering in military obscurity throughout the 1950s, that the role of the Special Forces was changed to include something for which it had not been designed —training.

Men of the 1st Special Forces Group arrived on Vietnamese soil on June 24, 1957, and began training 58 South Vietnamese soldiers at the commando training center in Nha Trang. Those trainees would form the core of the first Vietnamese Special Forces units. Nha Trang would eventually become the Special Forces main base, and the commando school would later be used to train LRRPs.

Preparing The “Savages”

The Special Forces began preparing the Republic of Vietnam for the soon-to-burgeon conflict in May 1960 and were given the counterinsurgency mission by presidential directive in 1961. Taking another lead from the French GCMA, the Special Forces focused their organizational effort on Vietnam’s mountain tribesmen and brought in troops from Fort Bragg, North Carolina, to train them.

The Montagnard tribes in South Vietnam —five main groups of 500,000 to 700,000 people each —contained some 20 distinct ethno-linguistic elements. Some tribes could not speak the language of their immediate neighbors, though all were tagged with the generic montagnard (French for “mountaineer”), since the tribes were essentially hill people. Lowland Vietnamese called them moi —”savages.” Most Montagnards lived in the Annamese Highlands of both the North and South. The principal tribes in the South were the Rhade, Jarai, Bahnar, Sedang and Bru. There were also tribes that had fled or emigrated from the North.

Special Forces troops approached the Rhade community in October 1961 and formed the first Civilian Irregular Defense Group (CIDG) at Pleiku. The concept of the CIDG program was similar to the GCMA, with an American leadership group usually comprised of a 12-man Special Forces A-Team. The units were stationed around the country and working out of their own fixed bases.

Reconnaissance and Intelligence

The A-Teams patrolled alone as well as with the company-strength Mike (mobile strike) Force units of the CIDG. It soon became apparent that intelligence-gathering was of supreme importance in Vietnam, and to that end the Special Forces organized several different types of units based on the A-Team concept to handle the long-range patrol missions required in gathering intelligence. For example, reconnaissance training for Project Delta, code-named “Leaping Lena” (a 1964 mission in which Vietnamese reconnaissance teams parachuted into areas near the Laotian and North Vietnamese borders to survey the Ho Chi Minh Trail), led to the development of similar units, including the Studies and Observation Group (SOG), Project Omega, Project Sigma, Project Gamma and the B-53 and B-55 detachments.

Major General Joseph A. McChristian, MACV assistant chief of staff for Intelligence under General William C. Westmoreland, said that the role of ground reconnaissance could not be overemphasized. Westmoreland himself believed that it “not only can provide timely and accurate information on all aspects of the enemy and the area of operations, but also can report on where the enemy and his influences do not exist.” The training of division-level LRRP teams was handed over to the 5th Special Forces at Nha Trang by General Westmoreland. The Special Forces had established the MACV Recondo School there in September 1966 and started training Regular Army unit volunteers in the long-range patrol techniques that it had learned in previous years from its Project Delta experiences.

Training LRPs

The Recondo (a name derived from the combination of reconnaissance and commando) course started out with 60 students per week in September 1966 but doubled by January 1967. It would train nearly all of the LRRPs who served in-country until it officially closed on December 19, 1970.

Also of importance to LRRP training at this time were instructors whose military heritage traced to the 2/2 Independent Company of WWII and the Anzac Special Air Service. Some LRRP units copied Australian tactics, others those of the Special Forces. The primary difference between the two appeared to be team sizes: Anzac training suggested three- and four-man teams, while SF trainers tended to form groups as large as six, eight and more.

The first provisional long-range patrol (LRP) units were formed in 1965 and 1966 at the divisional level, but it was in 1967 that the LRRP organizations flourished and became formally established. The acronyms LRP and LRRP soon were interchangeable, though most orders of battle refer to the units as LRPs. Most often, the men fighting in the Vietnam War referred to themselves as LRRPs (“Lurps”). Every integral Army group in-country, whether brigade or division level, had its own LRRP unit.

Major General William R. Peers, commander of the 4th Infantry Division, noted in 1967: “Every major battle the 4th Infantry Division got itself into was initiated by the action of a Long Range Patrol; every single one of them. That included the Battle of Dak To, for the Long Range Patrols completely uncovered the enemy movement. We knew exactly where he was coming from through our Long Range Patrol action.”

Dangerous And Uncomfortable Job

Lieutenant General John H. Hays, Jr., who commanded the 1st Infantry Division from February 1967 to March 1968 and went on to become the deputy commanding general of II Field Force, serving until August 1968, said that the LRRPs were “generally considered to have the most uncomfortable and dangerous job in Vietnam,” but also noted that “the way in which the long range patrols were used was one of the most significant innovations of the war.”

The typical unit consisted of 118 men —115 enlisted and three officers divided into two platoons of six- to eight-man teams, with the remainder being support people. The numbers varied widely —from units with as few as about 60 men to as many as 230 —as did the company makeup, the length of missions and the size of teams. Some operated in two-, three- and four-man teams, some 10. Some companies used a tracker. Montagnards were favored by most, but some used Vietnamese Rangers, scout dogs or Chieu Hoi scouts. “Chieu Hoi,” meaning “open arms,” was the name given to a program that induced enemy troops to surrender, retrained them and assigned them as scouts for infantry units —a tactic drawn from guerrilla wars fought in the Philippines, Malaya and Kenya. Terrain and operational requirements also affected the practices of the individual LRRP units.

The missions of the units encompassed other activities besides pure reconnaissance work. Setting ambushes, snatches (kidnappings), sniping, stay behinds (remaining on firebases after U.S. troops evacuated from them), on-ground photography and bomb damage assessment were all part of the LRRP repertoire.

Exemplary Record

A typical operation in which LRRPs were involved was Operation Uniontown III-Boxsprings, in which Company F LRRP, attached to the 51st Infantry (F/51), was working in conjunction with the 199th Infantry Brigade (Light) between the towns of Bien Hoa and Xuan Loc near Saigon in February and March 1968. In the course of 117 patrols, LRRP teams sighted enemy troops 91 times, required 40 emergency extractions, and exchanged fire with the enemy 33 times. The 199th exploited F/51’s enemy contacts with reaction forces 10 times. F/51 was credited with 48 enemy KIAs, 26 probable KIAs and 18 POWs —all while suffering no losses of its own.

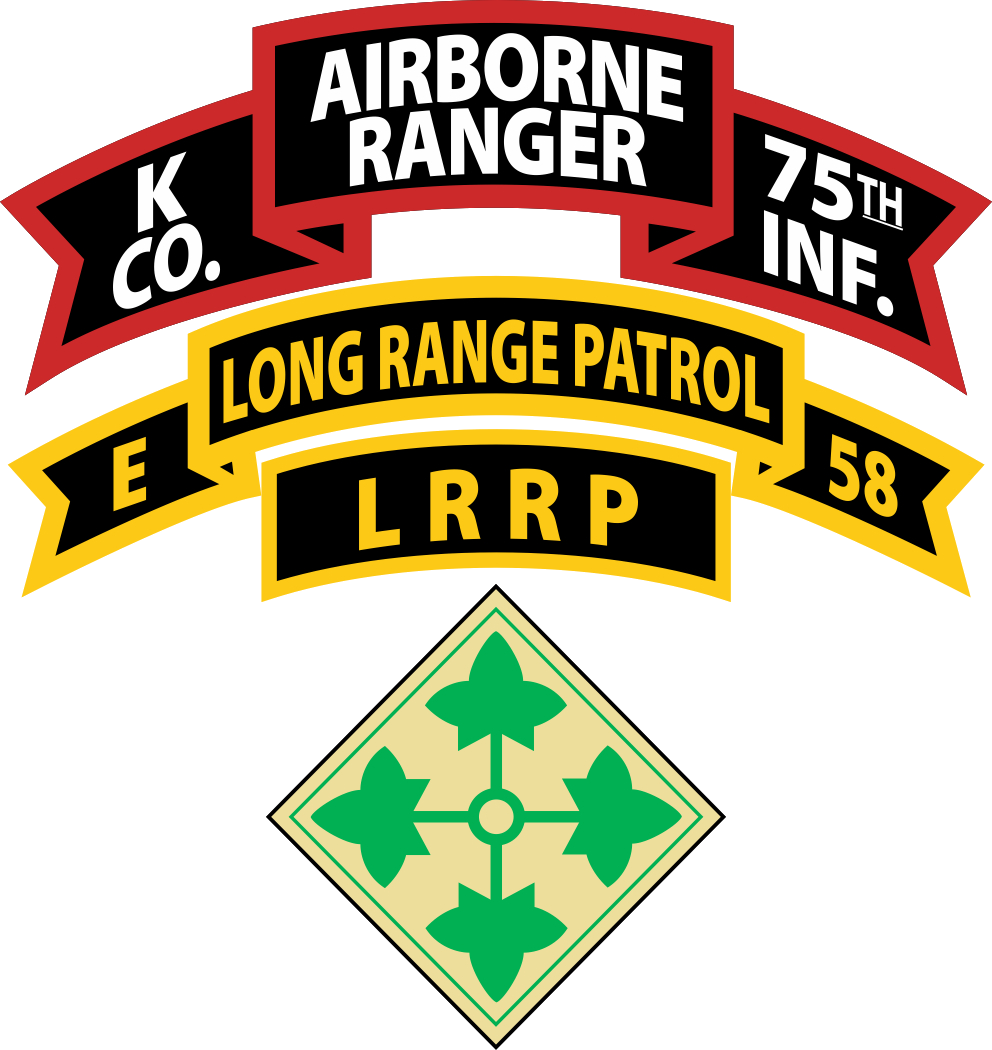

Divisional LRRP units achieved an exemplary record throughout the Vietnam War, and MACV recognized their success by changing their name. On January 1, 1969, General Westmoreland brought the 13 different LRRP units under the umbrella of the 75th Infantry Rangers, linking them to the 75th Infantry of 1954 and the 475th Infantry of 1944 and that unit’s 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) —Merrill’s Marauders —whose regimental patch the Rangers would wear. The LRP/LRRP companies would be designated from then on as companies C through I and K through P, 75th Infantry Rangers.

(Company D, 151 Infantry, an Indiana National Guard LRRP unit was not included — unfortunately — in the reorganization. Company D 75th Rangers [II Field Force] was activated to replace them when they ETS’d.— GPJ 11-5-19)

As direct American involvement in the war approached its conclusion and the manpower commitment of the military waned, the Ranger units began being sent home and deactivated with the units to which they were attached. First out was Ranger Company E of the 9th Infantry Division on August 23, 1969. Company L, the last Ranger unit in Vietnam, assigned to the 101st Airborne Division (Airmobile), was officially deactivated on December 26, 1971.