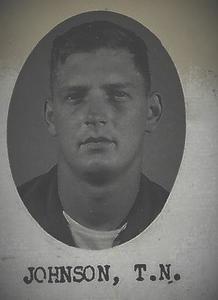

Terry N. Johnson

SGT – U.S. Army

4th Inf Div 2nd Bde LRRP

30 October 1943 – 30 July 1994

Pennsylvania

LZ OASIS, May 1968

Sgt. Johnson back at the Oasis from a “Jeep snatching mission” at Camp Enari

for the “provisional” 2nd Bde LRRPs

in Korea

with “Clyde,” the mad mascot monkey, Oasis, 1968

Platoon Sergeant Johnson, standing on TOC Conex at the Oasis – “training” his men

MILITARY DATA

Service: Army (Regular)

Grade: E6

Rank: Staff Sergeant

MOS: 11B40 Infantry

ID Number: 13795912

Len Svc: more than 5 years

Unit: 4 INF DIV, 2nd Bde LRRP – E/58th Infantry (LRP)

CASUALTY DATA

Start Tour: November 1967

Cas Date: N/A

Age at Loss: 50

Remains: N/A

Location: Maidsville, West Virginia

Type: Non-hostile

Reason: Black Lung Disease

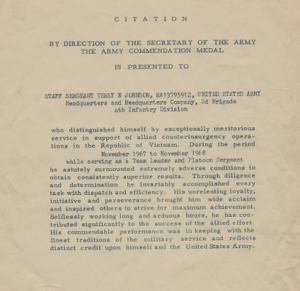

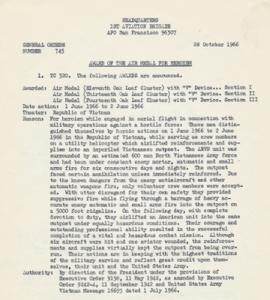

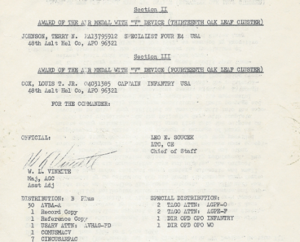

AWARDS

Combat Infantryman Badge; Army Commendation Medal; Air Medal w/14 OLC, 1w/V device; National Defense Service Medal w/2 service stars; Vietnam Service Medal w/8 campaign stars; Vietnam Campaign Medal; Aircraft Crewman Badge; SPS M-14

GRAVESITE

Mt.Morris,Pennsylvania

* * *

SSG Terry Johnson, was from coal country in Southwestern Pennsylvania and Northern West Virginia. He passed unexpectedly at the age of 50 from Black Lung Disease. Terry enlisted in the Army at 19 in August 1963. During 1964 he was then stationed one year in Korea with 2/5 1st Cav. In November 1965, as Specialist Four, he was assigned to the 25th Infantry in Vietnam, where he volunteered to be a helicopter doorgunner with the 48th Assault Helicopter Company. He spent all of 1966 with 48th. AHC. Johnson returned to Vietnam in November 1967 as a sergeant, where he volunteered for the 4th Division’s 2nd Bde LRRPs. He became a team leader and platoon sergeant. He was universally respected in the unit for his experience as a team leader who had lost no man on patrol – dead or wounded – and his fabulous teaching and mentoring skills. In July 1968, Sgt. Johnson was promoted to Staff Sergeant and transferred to E/58th Infantry (LRP) to act as platoon sergeant, until November 1968, when he returned to the States.

From his son Mark N. Johnson – markj5853@gmail.com – 25 April 2016

My dad only spoke about his service in Vietnam to a few people. I was one of those few. I always had many questions for him when I was a boy and he would answer me, sometimes. I was only 18 at the time of his sudden passing. Dad was a coal miner when he came back for 17 years and passed from complications from Black Lung at 50 years old. I miss him dearly. He was my teacher, my motivator and my friend.

Dad would tell me “I was a Door Gunner in 66 and a LRRP in 68”. I’d say dad whats a LRRP? Answer- the best men I ever knew .

My dad grew up about 1 hour south of Pittsburgh PA on a farm in small Davistown PA. He enlisted at 19 in August of 1963. Basic was at Ft Knox then on to AIT at Camp Crockett, Ft Gordon. He then spent all of 1964 stationed in Korea with 2/5 1st Cav. In 1965 he and my mom lived on base at Ft Hood. In November of 65 he got orders to Vietnam with the 25th Infantry Division. While with the 25th dad volunteered for Door Gunner duty and after some training with the 117th AHC he was assigned to the 48th Assault Helicopter Co and spent all of 66 with the 48th AHC.

November 66 dad went back to Ft Knox and spent most of 1967 there with some training at Ft Eustis. He went back to Vietnam in November 1967 with the 2D BDE 4TH Infantry LRRP. He went to E/58th Infantry LRP in July 1968 and was promoted to SSG.

I have only come to truly learn of my dad’s service in the past year and a half. I needed to find out what he did and what units he served with. November 11 2014 (My mom’s birthday) I started the puzzle. My wonderful mother Connie, who is doing great at 70, has been a huge help. She had dads DD214 and his yearbook from 1964 2/5 1st Cav Korea. I remembered the yearbook from when I was a boy and asking dad “why are these VC in this yearbook with you guys”. He said No, No the guys in the yearbook were our allies . He then told me many stories about the Montagnards during his time in 1968.

With his DD214 I read HHC 2D BDE 4ID. All this was foreign to me. Next I read 11B40 Sqd Ldr. I also noticed other things such as CIB, Air Medal w14 OLC (one w/V) and 4 o/s svc bars and several other interesting awards. As I looked up the different awards/badges I was shocked. Dad only had 3 of his medals at home NDSM, VSM and Air Medal. He was very proud of his Air Medal and would amaze me with stories in places like Ban Me Thuot and Tuy Hoa manning the gun. He also told me in 1966 is when he first heard of the LRRPs. He worked with the 101st Airborne LRRPs while with the 48th AHC.

When I would hear my dad say LRRPs I would pay very close attention. He mentioned names to me such as Robinson from Michigan and Harry Sweeney from Elizabeth WV, Flores from California and Posdniakoff from New York. He never told me he was a team leader but I knew the LRRPs were important to him. He dressed me in his Tiger Stripes fatigues and painted my face for Halloween in grade school. He said you can wear these once . I didn’t see those Tiger Stripe fatigues until my mom gave them to me about 1 year ago.

I did see group picture with my dad honoring the fallen. I am sorry for the loss of your brothers. I also enjoyed the video-it took me back to my dad barking orders at me to move rocks or dig that dirt for no real reason but to do it. He was very strict with me growing up and I wouldn’t have wanted that any other way. We were avid deer hunters up here in the Appalachian Mountains. When I was 8 I learned to shoot dad’s gun finally. Winchester 300 mag. We would walk for miles into the woods in the dark of morning. He would show me how to tie my boots like the LRRPs did. Secure all my gear for me like the LRRPs did so we didn’t make any noise.

I have learned so much the last few years about my dad’s service. Internet research, the Texas Tech Archives and my mom’s sharp memory have led me here. I share all this with my mom and our entire family who loved him very much.

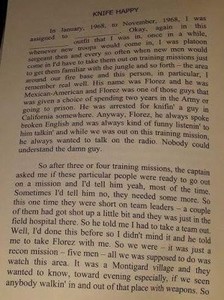

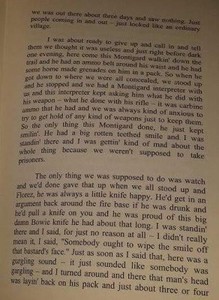

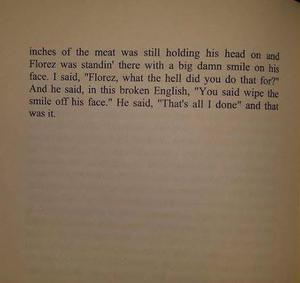

In around 1974 or 75, the local WV Junior College offered free courses to Vietnam Veterans. In a speech class the instructor brought in an author from southern WV. With the “students” approval, the author recorded stories from and the transcribed them on paper. The authors were listed in the front of the paperback but did not affix their name to their own story. My dad told me which one was his.

LRRP redacted.

I remember Sgt. Johnson – my first team leader…

Nick “Poz” Posdniakoff, 2nd Bde LRRP (Feb 1968 – Feb 1969)

I arrived at Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, a private first class from the 24th Airmobile Infantry in Germany, on January 30, 1968. After one year of volunteering attempts to fight the Communists, they finally let me go to Vietnam.

The very next day, the Communist Tet offensive began with a series of stunning multiple surprise attacks launched on Saigon by the Viet Cong. But, I was missing all the action while waiting for a unit assignment. In the confusion, while Saigon burned, the new replacements were left in their barracks, ignored and forgotten. Lying in my bunk, I listened to the explosive gunfire in the city and naively yearned to join the battle. The next day, I strolled through the quiet PX, empty of the usual G.I.s, eyeing the hefty black Rolex Submariner diving watches on sale for $130. With my new supplement of $65 per month for combat pay, I would be able to afford such a beautiful watch in just two months time.

I had volunteered for Vietnam to fight the Communists, but was assigned to a shit detail instead. The sergeant of this detail picked four newly-arrived troops and issued us each a long iron re-bar, bent almost double at the end, appropriately termed the shit hook. He tasked us with pulling out the 55-gallon oil drums that had been cut in half and positioned under the latrines in the camp. Once out in the open, we had to douse the noxious contents of each barrel with diesel fuel from a Jerry can, and then prime them with gasoline from another can. The mixture was set afire and allowed to burn for about an hour, depending on how full the barrels were. The sergeant, from a goodly distance away, ordered us to stir the burning contents from time to time with our bars until nothing but black cinders remained.

It was the 1st of February. Happy Birthday Nick! Welcome to Vietnam.

The thick, choking smoke from the fires enveloped us and stuck to our bodies for days. With hundreds of barrels in the camp, a shortcut seemed in order. So, when our sergeant was looking away, I doused my barrels with straight gasoline instead. The resulting explosion dropped him to the ground, and I was promptly taken off the detail. I wasn’t too worried, though.

What were they going to do… send me to Vietnam?

* * *

Finally, I was assigned to the II Corps Tactical Zone’s Fourth Infantry Division in Pleiku, Central Highlands; but I was still missing all the action of the ongoing Tet battles while sitting in Camp Enari on Dragon Mountain, waiting for placement in an infantry unit. Just a few days before, the enemy had struck the Highland cities of Kontum and Pleiku, attempting to penetrate their military compounds; but very quickly, the VC’s offensive had suddenly turned into a defensive fight for their lives. The Fourth Division had attacked them hard instead. In the end, the enemy in our area of operations would lose nearly 3000 troops, the United States fewer than 50, and the South Vietnamese forces approximately 145 – all in just one week.

At night, I would sneak out of our “repo-depot” barracks at Camp Enari and make my way to the bunkers on the barbed-wire perimeter to watch the sandbagged Dusters (M-42 Self-Propelled Anti-Aircraft Guns), and M-60 machine-gunners shoot out into the darkness in front. The rhythmic soft thuds of the impacts of the 40mm Duster rounds in the distance had an almost musical repetition to them, while the sporadic, louder blast of an artillery piece, or harsh rattle from a nearby machine gun, shattered the tempo of the malevolent melody. It was a mad cacophony of angry sounds, as if directed by a mad conductor waving his deadly wand somewhere close nearby. Sparks flickered in the dark skies above us, ominously in exact time with the outgoing gunfire. Bright tracers criss-crossed over our heads, falling lazily to the ground like accidental meteors.

I sat on top of the bunker with the other G.I.s, shivering in the cold winter air of the Highlands, awestruck. The teenaged grunt next to me, pointed his M-16 at the tracers, and gasped…”Far out!”

He sucked hard on the joint before passing it around. Tet was finally over.

So, this is war… I thought.

The week that followed was a refresher course in the field how to conduct a search & destroy patrol, identify enemy booby-traps, and show us what a Viet Cong actually looked like. Some of us, trained for military service in Germany, had never even seen the new M-16 rifles being used in Vietnam. At the firing range, we wondered about the fragility of the plastic stock, and fumbled with the weapon’s awkward charging handle and unfamiliar forward bolt assist lever used to seat the cartridge properly in the chamber.

Finally, I received my orders to join the Second Brigade’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry Regiment as a rifleman, but on the way to check in with the company clerk, I noticed a captain in camouflaged jungle fatigues and dapper Aussie bush hat making a presentation to the troops at a nearby assembly area. He was looking for highly motivated volunteers to join his special unit to conduct dangerous missions in the jungle, the Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol, or L.R.R.P.s – pronounced “LURPS” guardedly by the troops.

After being inserted behind enemy lines, these five-man teams would collect battlefield intelligence, scout out the location of enemy troops and base camps, conduct terrain analysis, act as trail watchers, or snatch prisoners to bring back for interrogation. The regular troops, aviation, and artillery of the Second Brigade would then engage and destroy the enemy troops and base camps. The L.R.R.P. recce patrols were referred to as missions because each one had a specific set of carefully planned-out objectives. Just the kind of job I wanted, especially if it involved finally catching some real Communists.

The interviews and selection process for the L.R.R.P.s were rigorous, but my college background, advanced infantry training in Germany, and jungle experience in Hawaii helped get me in. One week after my 22nd birthday, the L.R.R.P’s commanding officer, Cpt. Tom Garnett, invited me to join them. However, my acceptance was provisional – whether I stayed would depend on my performance during a few trial missions in the jungle.

The Second Brigade L.R.R.P.s, a 60-man strong unit, was established at LZ Oasis firebase, 24 kilometers west of Pleiku. It acted as the eyes and ears for the Brigade’s 3000 men spread out along the border. Our camp was near the hamlet of Thanh An on Highway 19, which led 35 kilometers into Cambodia. This was an area where the Ho Chi Minh Trail branched out from neutral Cambodia and ended in individual smaller infiltration routes used by the NVA to enter Pleiku Province clandestinely at night.

A U.S. infantry platoon or company stumbling around in the jungle searching for Charlie typically never found him, until it walked into a well-placed ambush. This is why the Fourth Infantry Division needed a special entity comprised of stealthy five-man recce teams. The L.R.R.P.s.

On the books, our unit consisted of ten five-man HAWKEYE patrol teams, but with a constant flow of wounded and rotating personnel, we typically fielded no more than seven recce teams at a time. Teams Hotel-2-Alpha, Hotel-2-Bravo, Hotel-2-Charlie, Hotel-2-Delta, Hotel-2-Echo, Hotel-2-Foxtrot, Hotel-2-Hotel … I noted a sign prominently posted in front of the L.R.R.P. compound; a casualty numbers board. It showed a 50 to 1 advantage in enemy kills favoring the L.R.R.Ps.

Great… I thought; this job didn’t look as dangerous as it sounded.

As the incoming FNG (Fuckin’ New Guy), I was assigned to L.R.R.P. team Hotel-2-Delta, led by Sgt. Terry Johnson, who was to take me out on a mission near the trail system to check for any enemy movement, and see if I passed muster during the next five days of patrolling. It was not long after the grueling battles of Dak To and Tet attacks on Pleiku, so the major enemy units had been bloodied and were expected to regroup and withdraw to neutral Cambodia for rest and resupply. Thus, our mission was routine, to confirm their departure.

My job was to carry the radio, stay glued to team leader Johnson, and pass him the handset for communications whenever required. Johnson instructed me not to fire my weapon, or even look at the enemy, just follow him closely, and do exactly as he ordered. Sgt. Johnson was a big husky trooper, a bit overweight around the middle, and I was sure that I could easily keep up with him. After months of field exercises in the Bavarian mountains, I was in great shape.

We were going in by helicopter at first light. The team’s point man, William Corbitt, a former trapper of alligators in the Everglades swamp – better known as “Shortie” to his close friends, or the “Gator Man” to the others – took me under his wing to explain the mission and what had to be done. He helped me sort out the equipment that he carefully laid out for me on my bunk. I was issued a combat kit that included a CAR-15 5.56mm submachine gun version of the standard M-16 rifle, and 21 magazines loaded with just 17 rounds each instead of the normal 20. The new CAR fired so fast, over 800 rounds per minute, that the magazine springs were often too weak to feed the cartridges properly, and there was a risk of jamming if loaded fully. My mentors taught me to tape a cleaning rod to my fast-firing CAR; this way, if a casing jammed in the receiver, I could knock it out quickly and continue firing. In comparison, the NVA’s slower-firing AK-47s held 30 round banana clips that worked just fine.

Also, since troops in Germany were trained on the heavier M-14 rifle, I was not yet familiar with the new M-16s and lighter CAR-15 carbine versions being used in Vietnam. Neither had I adapted yet to carefully squeezing off three round bursts with the CAR to make the magazines last and to better hit the target.

My other equipment consisted of web gear with suspenders hooked up to four old-style M-14 ammo pouches, each holding five 5.56mm CAR magazines (for a total of 400 rounds). Four frag grenades were taped to the front ammo pouches, while a couple of CS grenades and Willie Petes hooked on the back pouches. I also strapped on my personal Gerber Mark II combat knife, and a .380 Cal. Llama automatic pistol that I had brought with me from Germany against Army authorization.

Also on my bunk was a PRICK 25 (Model AN/PRC-25) radio set that, not surprisingly… weighed exactly 25 pounds, along with two large spare battery packs, each one resembling a carton of cigarettes, but full of lead instead. There was a one-meter-long flex metal whip antenna that would be connected to the radio during patrol movement, one three-meter-long collapsible fishing pole antenna for communicating from a fixed position, and a roll of commo wire for setting up a long-range T-antenna. In addition, I was given a spare handset, an SOI with radio frequencies for contacting artillery support units in the AO, and a tiny URC-10 survival back-up radio for signaling our aircraft in an emergency.

Other gear included a claymore antipersonnel mine, several smoke grenades for signaling, a few more baseball frag grenades, a packet of C-4 plastic explosives with det cord and blasting caps, and a parachute signaling flare. I also slipped three cans of peaches and a tiny, handy, folding army P-38 can opener into my pack. Peaches were my favorite military rations; I would trade cigarettes for them with the smokers in my unit.

Finally, my teammates dumped some additional items on my cot, including a section of Goldline climbing rope, five canteens of water, a dozen dehydrated L.R.R.P. rations, rubber poncho and nylon poncho liner, spare socks, first aid kit, can of serum albumin blood expanding plasma, iodine water purification tablets, malaria pills, an orange ground signal panel and pen gun flare kit, strobe light, flashlight, bug juice, watch, map, notebook, pens, signaling mirror, and two compasses…

My new teammates helped me stow all these items in specific pre-designated locations into a modified North Vietnamese army rucksack, and then had me jump up and down with the pack on to check for noise. Sgt. Johnson tossed me a large roll of sticky green cloth tape to secure any loose items. Not including my weapon and combat kit, my rucksack easily weighed 80 pounds. Now I understood why the infantrymen in Vietnam were known as the grunts that was the noise they made when lifting their heavy packs from the ground!

I was carrying a total load of 100 pounds of weapons and supplies to last a week in the jungle, while my own body weight was 165. My teammate Shorty weighed 130 pounds and his pack was as heavy as mine! At least I didn’t have to wear a steel pot any more, having exchanged my heavy infantry helmet for a soft floppy hat, and a set of extra-large South Vietnamese army tiger-stripe camouflage fatigues.

* * *

We were off just before dawn, five men with blackened faces, loaded down with weapons and gear. On the helicopter pad, we carefully cross-checked our equipment over and over again, and then climbed on the smoke-belching dark green bird that seemed to be whining with impatience to leave the ground with or without us. Soon, we were whirling past the little yellow and brown agricultural squares below us, clicking along rapidly one by one, to the foothills, and the dense green expanse of the jungle near the border. After making several false insertion maneuvers to confuse any enemy observation, the slick prepared to drop us off at a small previously selected clearing in the jungle, while two Cobra helicopter gunships criss-crossed low around us to provide fire support.

We had previously checked and chambered our weapons; they were ready to fire. I had a hundred questions to ask Sgt. Johnson. My first combat mission.

What do I do once reaching the ground? When do I set up the radio? What if the enemy was already waiting for us there? What if they start shooting? What if my new, unfamiliar CAR-15 jammed? What do I do then?…

Signaling me to follow from my canvas seat by the bulkhead, the men moved over to the belly of the aircraft, next to the open hatches, sitting on the metal deck with their feet hanging over the sides, ready to jump off. The noise of the rotor and gusts of wind made speech impossible, and anyways, I could no longer remember what I had wanted to ask the team leader. It seemed so important at the time…

Heart pounding from the adrenaline rush, I looked at the rapidly approaching ground covered by high elephant grass swirling around in a mad green dance just a few meters below us. The chopper hovered in place momentarily and I mechanically followed my teammates, who leapt off the skids in a determined rush, weapons extended out front, into the dark green sea of vegetation that was moving around us in an angry and menacing sway.

I did not realize for how long I dropped through the tall grass, several meters at least, but the heavy load on my back dumped me unceremoniously upside down on the ground with an unexpectedly hard jolt. The metal stock of my CAR was jabbing painfully into my ribs. I was stunned, unable to move. Did I break something?

I could feel Sgt. Johnson’s impatient hands shaking me roughly around to get my pack open and quickly reach the radio. He had to contact the helicopters and confirm our exact drop location on the map before clearing them to depart the area.

We then moved slowly away from the LZ and set up a defensive position for an hour-long motionless wait to see if our insertion was clean, and get used to the jungle around us. After the numbing noise of the chopper ride, the jungle surrounding us was deathly quiet.

Finally, we started out, moving very slowly, one step at a time, with the point man in front, then Sgt. Johnson about ten meters back, me with the radio sandwiched directly behind him in the middle of the patrol, then the ATL, and rear security spaced out last. As we moved slowly through the heavy brush, making no noise whatsoever and avoiding all trails, I started to feel the weight of my pack as well as my brand-new stiff jungle boots that were quickly chafing my feet into a mass of blisters. I was not used to the terrain either, and had to keep my eyes constantly on the ground to keep from tripping over the vegetation. Soon, I was huffing and puffing, barely keeping up with Sgt. Johnson, just a meter in front, whose heavy frame moved along with an ease and agility I envied.

By late afternoon, we had discovered a series of fresh trails, which we skirted in parallel for security’s sake, since this area had no civilian population. We heard the sound of wood being chopped in the distance and smelled smoke from camp fires. These two unmistakable indicators of close enemy presence would haunt me for the next year, each time evoking the same immediate reaction of anticipation, caution, and lingering dread.

The team was quickly becoming very anxious. The point man stopped and whispered excitedly to Johnson that he saw the flash of green uniforms and pith helmets ahead: a squad of NVA! My eyes, constantly fixed on the ground before me, saw nothing at all. More trails intersected our path, well used, and described by Johnson as high speed during our next radio contact with the Oasis. We were walking into an NVA base camp that was clearly in use. It was time to pull back and observe.

The team was getting more and more on edge as we tried to move quietly away from the NVA base to find a high point from which Sgt. Johnson could call in an artillery or air strike on the enemy position. But it was getting dark, and the terrain forced us to descend away from the NVA instead of gaining cover above them. The team leader wisely decided that it would be safer to find a secure night location and engage the enemy in the daytime. We crawled on our hands and knees with heavy packs on our backs into the thick jungle; Gator, the point man using a small pair of garden shears to silently shape a narrow tunnel in the dense foliage for us. The last L.R.R.P., on rear security, crawling backwards, carefully covered up our tracks behind him.

We were well concealed in a thicket, but not very far from the NVA trails above us. We set up claymore mines around the perimeter for security, and the team formed a tight circle with the radio placed in the middle, at our feet. Sgt. Johnson stretched out his bulky frame next to me, where he could check up on me easily in the dark. We ate our rations cold, reluctant to use our little heating tablet stoves. The tablets burned with a distinctive acrid chemical odor that could compromise us.

I replaced the radio’s short whip antenna with the three-meter-long rigid fishing pole that clicked together like tent poles, and Sgt. Johnson whispered the coordinates of our night location to the Oasis. He also arranged a possible extraction for the next day by re-confirming the location of a pre-planned LZ that was about 500 meters below our bivouac. After the sitrep radio call, Johnson rehearsed with all of us the exact compass bearing of our escape route to the LZ, in case of an emergency during the night, and a final rally point if any of the team members became separated in the dark. The entire team worried that the NVA was already on our track, while I had not a clue that we were even in any danger. My feet were killing me and I removed my boots to survey the damage. I was exhausted. It was pitch black now, but everyone was awake and jumpy.

What the hell is everyone so worried about?… I thought to myself.

An hour later, when I was just starting to doze off, I felt Sgt. Johnson’s hand suddenly brush up against my right arm, clasping my wrist in a soft but urgent grasp. It was our danger signal in the dark! I sat up instantly alert, heart pounding, trying to gather my senses. A line of flashlights blinked dimly several hundred meters away on the ridge above us, creeping slowly and steadily down towards us. The NVA were looking for us!

My teammates were packed and ready in an instant, rolling up the claymores, and weapons in hand. Sgt. Johnson was already on the radio urgently whispering a request for our night extraction from the LZ below us. Choppers from the Oasis would be on station in 20 minutes and we had to get to the LZ in the dark by compass bearing alone. The team was already moving out. I was still packing up the radio and getting my boots laced. First, I had to remove the long rigid fishing pole antenna from the radio, fold it up, and replace it with the short flexible metal whip.

I was nervous. I couldn’t see a thing in the dark, and my hand was shaking as I groped around, feeling for the terminal connection. Johnson was tugging impatiently on the handset swearing at me to get my ass in gear. I was trying to find the tiny hole in the dark and screw in the whip, but was already being propelled forward, pack wide open and in my arms, through the dense underbrush. I was juggling both antennas loosely in my hands, while my slinged weapon was dragging from my shoulder. My shoelaces were still untied…

No one worried about maintaining noise discipline anymore; we had to find that LZ quickly. In the confusion in the dark, I accidentally dropped the thin, slippery metal whip antenna to the ground, and while pushing through the vegetation, the fishing pole antenna in my other hand unexpectedly opened up and locked with a distinct…

Click… Click… Click…

It became stuck in a bush, and I dropped it as well while desperately hanging on to my pack, trying to keep up with Johnson, who was crashing heavily through the brush in front of me. Incredibly, we all stumbled into the LZ in the dark, faces and arms torn up by the jungle. We could hear the incoming choppers already thudding steadily towards us.

Johnson was talking excitedly into the handset to guide in the helicopters that were looking for us. Nothing. He noticed the radio in my open pack… no antenna! He shouted at me to screw it in. I gave him a weary grin and pointed to the pack and the jungle behind him. Johnson was furious. He grabbed my wrist, spat on the antenna terminal, and pressed my thumb down hard to make contact with it. My body briefly became the antenna and the handset stuttered… the pilot came on the air asking for directions. Johnson told him to look for our strobe light that would mark the landing.

Johnson ripped off my hat, took out his strobe, turned it on, and put it inside. He shoved the hat into my hands and then pushed me forcefully out into the center of the clearing. I stood there in the open like the statue of liberty, hand stretched out to the sky, with the strobe blinking rapidly, while the helicopters quickly homed in on our brilliantly flashing white light.

The first bird dropped down quickly towards us. The pilot turned on his floodlights that illuminated us like the sun. The blast from the rotor was deafening and kicking up dust in our faces; we were blinded by the spotlights, when suddenly one of the door gunners opened up with his M-60 machine gun, the long muzzle flash reaching towards us. Was he shooting at us?

The team scrambled madly onto the chopper while I stood, dazed and confused by the gunfire, still holding the flashing strobe in my hat. Sgt. Johnson, an angry look on his face, tossed my pack with the radio on the slick and pushed me up the skid after it. He jumped on behind me, last man on board, and gave the pilot the O.K. to lift off.

As we rose, I saw green tracers arcing casually towards us, and muzzle flashes sparkling on the ridge. Both door gunners were firing frantically towards them, and so were some of the L.R.R.P.s with their CAR-15s. Exhilarated, I fired my CAR into the darkness below along with my teammates. It was a miracle that with all the confusion and firing not one of us had been hurt.

I was really going to like the L.R.R.P.s.

* * *

The next morning, however, I found my old steel pot on the bunk and was told to turn in my CAR-15 and other gear. Looked like Sgt. Johnson had made his report about my performance on patrol and I was being sent back to Camp Enari in Pleiku to rejoin my old line unit. Miserable, I contemplated the future.

Rejected by the L.R.R.P.s, I was waiting for the supply truck to take me away. Another team leader, Sgt. Leonard Valeen, a tall, well-built Californian, in his 20’s, with unruly black hair and an angular, inquisitive face, entered the tent looking for a volunteer to join his team, “Hotel-2-Charlie,” on a patrol to replace a member who had been wounded. I jumped at this chance and did everything I could to persuade him to take me along. Valeen was skeptical, but came back later when he could not find another body. He had talked to the CO and received permission for my second trial mission.

Cpt. Garnett had given me another chance.